Hospital leadership as healthy food advocates

Takeaways

- Hospital leaders, especially those at the executive level, are playing a critical role in steering their facilities to address the root causes of health.

- Food insecurity is a major public health issue and has implications for community health, clinical care, and rising health care costs.

- Food insecurity and other unmet social needs are associated with increased prevalence of diabetes and high cholesterol, higher use of the emergency department, and no-shows to clinic appointments.

- Investing community benefit resources in food security and healthy food access contributes to community health improvement and is good for the bottom line, with the return on investment taking many forms.

- Food insecure individuals have significantly higher health care costs, totaling $77.5 billion/year in the United States.

- Addressing food insecurity is associated with significantly lower health care expenditures and reduced likelihood of hospitalizations and nursing home admissions for seniors.

- Creating an engaged workforce improves retention rates and decreases absenteeism.

- Investing in community health improves community relations.

- Driven by their explicit mission to treat the sick and promote wellness, hospital executives, administrators, clinicians, and other leaders are increasingly committed to addressing social needs as part of clinical care.

This opportunity brief will help community benefit staff make the case to hospital leadership that programs and services that address food insecurity and healthy food access are a solid investment in not only the health of the community but also in the economic sustainability of the institution.

Social determinants of health are the economic, social, and environmental conditions that impact health, such as food insecurity, housing and utilities, education, and transportation. These factors may fall outside of the health care system and yet they largely determine a person’s overall health. Only 20 percent of health can be attributed to medical care, while physical environment and social and economic factors account for 50 percent.

The social factors driving health outcomes and health care costs cannot be ignored. A study by Massachusetts General Hospital in conjunction with Health Leads found that unmet social needs are associated with:

- Nearly twice the rate of depression

- 60 percent higher prevalence of diabetes

- More than 50 percent higher prevalence of high cholesterol and elevated hemoglobin A1c, a signal of diabetes

- More than double the rate of emergency department visits

- More than double the rate of no-shows to clinic appointments

It is important that hospitals begin to bridge the gap between clinical care and community health and high-level institutional champions are critical for health systems to start and succeed in this process.

Leadership (especially at the CEO level) with a strong understanding of and commitment to addressing the root causes of health has been identified as a key facilitator in hospital investment in community health.

Hospital leaders championing these investments would find themselves in good company. A recent study by Deloitte Center for Health Solutions indicates that 80 percent of hospital respondents reported their leadership is committed to addressing social needs as part of clinical care.

Talking point: Root causes of health

Social factors contribute most significantly to health and cannot be overlooked if health care facilities hope to make a significant and lasting difference in the long-term health of their community.

“Only 20 percent of health can be attributed to medical care, while physical environment and social and economic factors account for 50 percent.”

Learn more:

Making the case to leadership

Food insecurity and health outcomes

Food insecurity is a major public health issue and has implications for community health, clinical care, and rising health care costs. According to Feeding America, 41 million people in the United States struggle with hunger, including 13 million children and 9.8 million older adults, resulting in widespread effects on physical and mental health:

- Lack of access to enough healthy food is associated with higher rates of nutrition-related chronic diseases, like diabetes and high blood pressure.

- Food insecurity is associated with significantly greater emergency department visits, inpatient hospitalizations, and lengths of hospital stays. It can also mask underlying conditions or present symptoms that clinicians may misinterpret.

- Not having enough healthy food has serious implications for children’s health and development, and increases their risk for chronic illness and behavioral problems.

- Older adults with food insecurity are more likely to experience heart failure, asthma, heart disease, and depression.

Increasing access to healthy food has been shown to be effective in improving eating habits and reducing the risk for diet-related diseases. However, there are still over 40 million people living in neighborhoods without easy access to fresh, affordable, nutritious food options. As anchor institutions committed to improving the health and wellness of those they serve, hospitals are well positioned to play a key role in addressing community food insecurity and healthy food access.

Community health is a good investment

More hospitals are getting involved in addressing social determinants of health, and those established in this arena are starting to track quantifiable health outcomes and cost savings to determine the return on investment (ROI). This is still an emerging area of research, but there is already a clear business case for the health sector to invest in the root causes of chronic disease, and specifically healthy food access.

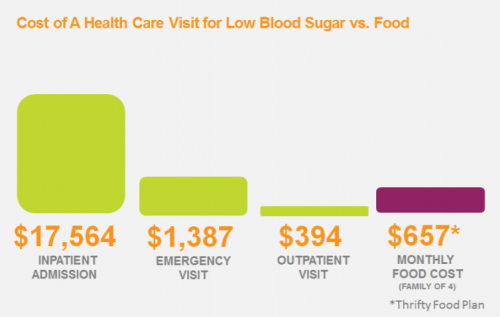

Improving food access would lead to reduced health care costs due to decreased inpatient hospitalizations, length of hospital stays, and emergency room visits - related to both food insecurity and chronic disease.

New research on food insecurity and health care utilization and expenditures indicates that food-insecure individuals have significantly higher health care costs, equivalent to $77.5 billion each year. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participation and access to healthy food, on the other hand, was associated with significantly lower health care expenditures (~-$1,409 annually/patient), and reduced likelihood of hospitalizations (↓14 percent) and nursing home admissions (↓23 percent) for seniors.

Hospital-level examples also demonstrate the success of healthy food programs to decrease the need for medical care. Geisinger Health System in Central Pennsylvania recently opened the Fresh Food Pharmacy which offers food insecure, diabetic patients a “prescription” for free foods that will help them manage their diabetes.

The fresh food is accompanied by education on nutrition and meal preparation, along with one-on-one meetings with health providers like registered dietitians. The annual cost per patient is $1,000 and preliminary data shows that participants in the Fresh Food Pharmacy improve their hemoglobin A1C (indicating improved management of diabetes) by an average of three points or the equivalent of a $24,000 reduction in medical expenses.

Talking point: Return on investment

Investing in community health is good for the bottom line, and the ROI takes many forms.

“Investing in improved healthy food access leads to reduced health care costs due to decreased inpatient hospitalizations, length of hospital stays, and emergency room visits.”

Learn more:

-

Northeastern University - “Population Health Investments by Health Plans and Large Provider Organizations — Exploring the Business Case”

-

Becker’s Healthcare - “How Investments in Community Health Pay Off”

-

Harvard Business Review - “Why Big Health Systems Are Investing in Community Health”

Hospitals are mission-driven organizations

While hospitals may have a business case for investing in healthy food access initiatives, this strategy is also informed by their mission. Health care is the only sector with an explicit mission to treat the sick, and hospitals commit to improving the health and lives of those they serve. While there are many iterations of hospital mission statements, it is common to find commitments “to heal,” “to improve children’s health,” and “to advance the health of communities.” Considering this mission, along with the cost of not addressing the root causes of health, hospitals have a moral and business imperative to address social determinants of health.

Talking point: Mission to heal

Hospitals have a moral imperative to address social determinants of health like healthy food access.

“Health care is the only sector with an explicit mission to treat the sick and promote wellness.”

Learn more:

- American Hospital Association - “Food Insecurity and the Role of Hospitals”

- Brookings Institution - “Hospitals as Hubs to Create Healthy Communities”

- Healthcare Financial Management Association - “Providers Focus on Food Insecurity”

An engaged workforce

Staff members at hospitals that invest in community health and address the social determinants of health may feel more inspired, committed, and engaged in their work. A theme that emerged in research interviews for Health Care Without Harm’s national community benefit study was that hospital staff across departments were proud and enthusiastic to be part of health care organizations that make a difference in the community.

For example, ProMedica, a nonprofit health system in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan, was an early champion of addressing food insecurity in their communities. ProMedica’s chief advocacy and government relations officer, Barbara Petee, observed that among the many good reasons to address hunger as a health issue is the gratitude hospital staff feel when they see how individual lives are changed.

Having engaged employees, who have an emotional investment in the hospital and its goals, results in benefits ranging from decreases in medical errors to reductions in staff turnover and absenteeism.

Learn more

- Through cross-sector partnerships, the Root Cause Coalition works to address the root causes of health disparities by focusing on hunger and other social determinants as health issues. The coalition was founded by ProMedica and the AARP Foundation. This white paper by Randy Oostra, the president and CEO of ProMedica, makes the case for “Becoming True Care Integrators to Improve Population Health.”

- The Social Interventions Research & Evaluation Network (SIREN) has a database of research that will advance efforts to address social determinants of health in health care settings. The network is supported by Kaiser Permanente and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and housed at the Center for Health and Community at the University of California, San Francisco.

- This Health Care Without Harm brief provides research and guidance for making the case to administrators that hospital investments in a sustainable food system may reduce disease burden as well as financially benefit individual hospitals and health systems.

- Practice Greenhealth has found that the most successful sustainability programs have significant support from health care leadership. The organization's website houses resources on engaging leadership as well as articles and presentations that highlight the synergy between community benefit and sustainability activities.

- The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation developed an issue brief that provides examples of community investment practices from pioneering hospitals. The aim is to inspire consideration of a broader range of options for addressing the social determinants of health.